Calvin Klein's Women

Thirty years after I was design director at CK its branding remains similar in a world with changed ideas about sexuality and identity...

This was written for and first published by The Miami Herald, in tandem with the publication of the Calvin Klein book (Rizzoli, 2018).

Did Calvin Klein empower women, or was he just another sexist?

“I never sought to shock for shock’s sake” Calvin writes in his book that depicts often naked women as sexual, empowered, and independent.

I was director of design at Calvin Klein from December 1990 till October 1993. Calvin hired me to create a collection that would compete with Donna Karan’s DKNY. During my first interview, he seemed annoyed that the younger urban customer, whom Donna had cultivated, had escaped him for several years. By the end of our second meeting we joked that we were going to start CKNY. Never once did he mention his daughter Marci. In fact her name did not come up until an editorial in Bazaar eighteen months later, in which Calvin said she was the inspiration behind the CK collections. My design team and I looked at each other in disbelief and laughed; Who the fuck was Marci? He’d never even told us he had a daughter who was like us! As I read Calvin’s book twenty-five years later, I laughed again. In Calvin’s inimitable style of myth making, his elusive daughter, and not Kate Moss, my all-women design team, or me, is credited as the woman behind the CK brand.

People often asked me what was up with his marriage to Kelly. Isn’t Calvin Klein gay? They’d say. But Calvin’s life is not so black and white --it’s generally the perfect hue of warm grey. Kelly is another strong, talented and independent woman. He was lucky to have her by his side in the nineties, when his brand was flagging, and the world had been wondering whether he too might succumb to AIDS. He did the opposite by marrying Kelly. He bought her Wallis Simpson’s ring inscribed with the words Eternity by Prince Edward and used this “royal” ethos for his next perfume launch, while calling Kelly his muse. The world swooned at this romantic myth and Eternity became a bestselling scent.

Calvin calls himself nonconformist as well as rebellious, which means he draws no lines, nor does he question his impulses or instincts. Why would he? When decisions didn’t work out, they weren’t mistakes. He simply changed course, cancelled entire collections, ended relationships, fired people, and hired others. It was all the same to him and a reflection of his constant and frantic push forward, towards perfection. Calvin prides himself on never looking back and appears unaware or desensitized to what this might do to others. Those willing to dedicate their lives to him. He might think it’s their problem as paths cross, times change, and people move on. I don’t necessarily disagree, but you had to be strong to withstand him.

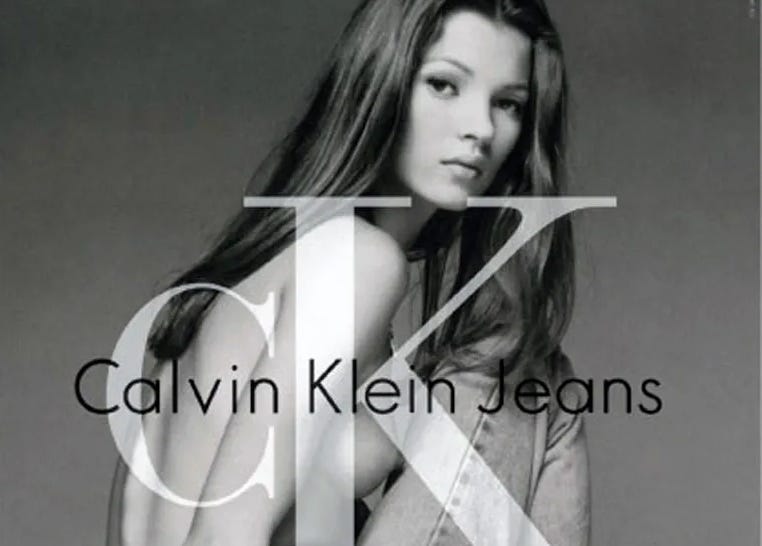

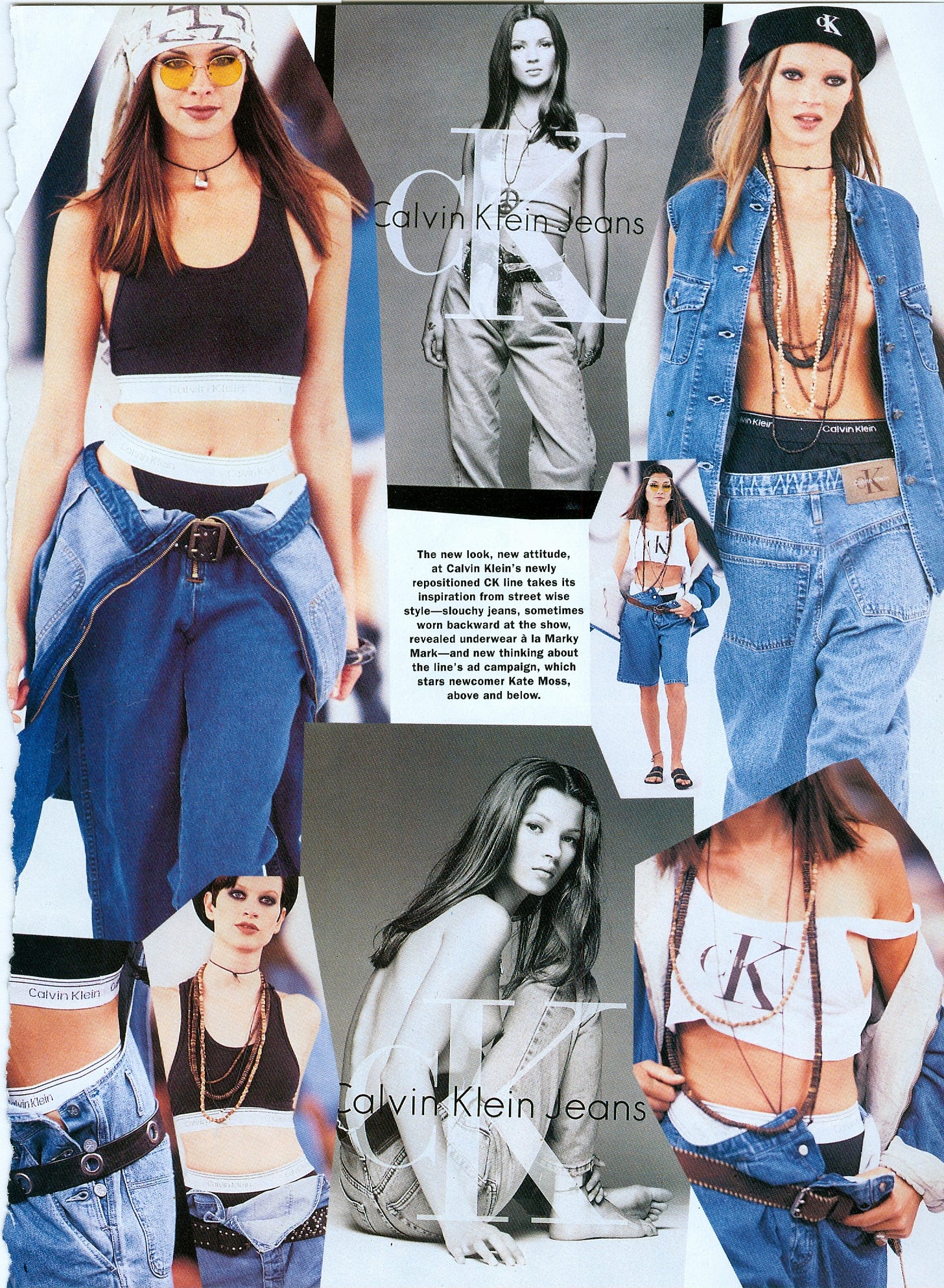

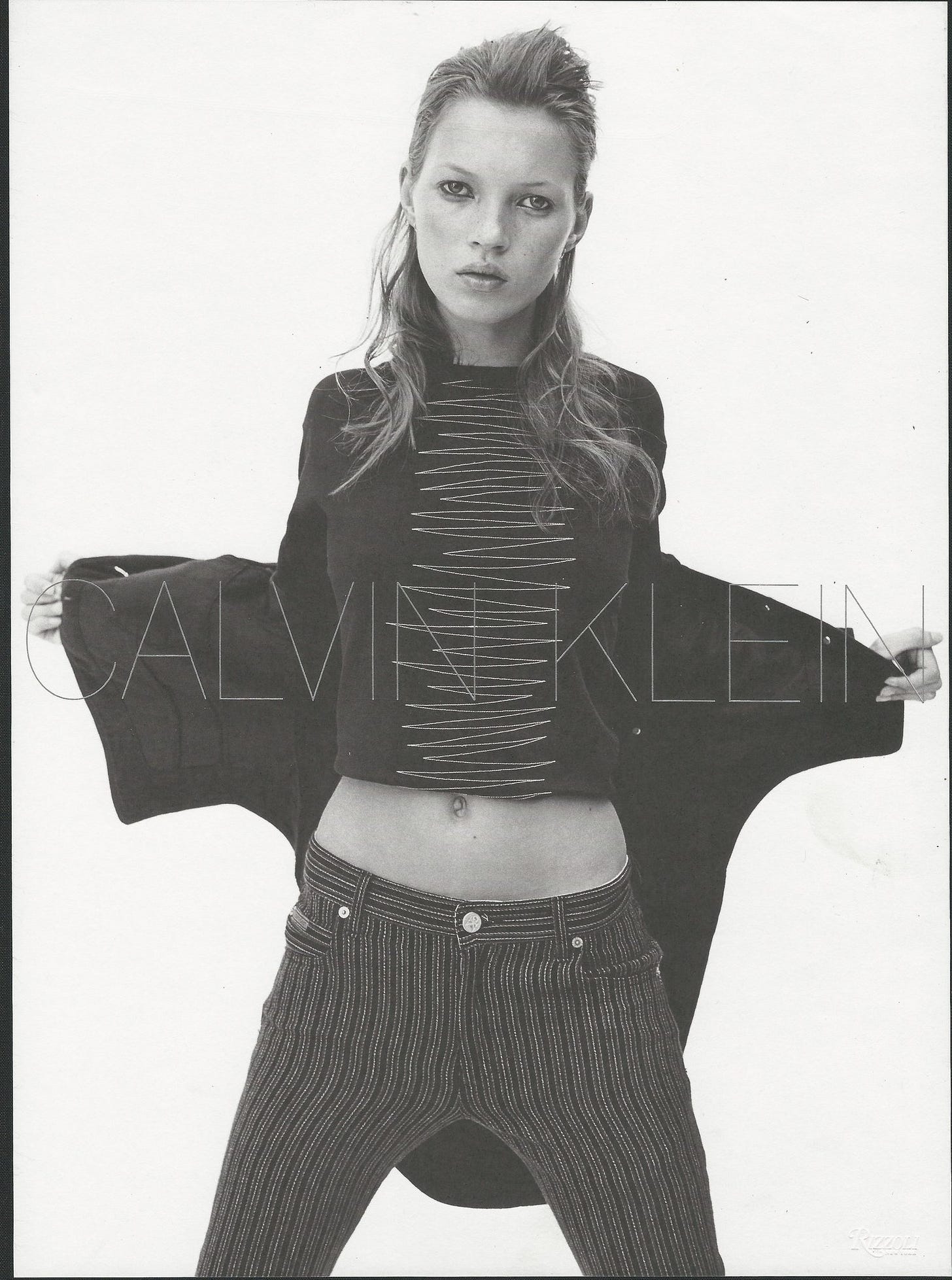

When Calvin sold the company in 2002, I wondered what he would do next. Who he would be. He’d always done what he loved. He’d lived his work. Over 30 years he’d successfully transitioned from a party-boy designer to husband designer to superstar designer, but I couldn’t imagine him as a retired designer. I thought he’d be miserable, cast adrift and surrounded by all the wrong acolytes. So I hoped that his book would show me the next incarnation of Calvin. That he’d inspire me once more, but all the nudity notwithstanding, nothing new was revealed. It is simply a handsome documentation of his work until he retired. It was nice to see just how much of our early CK pieces were featured, like the Kate Moss cover, where she wears mourning stripe jeans and a black jean jacket with tails. And the CK jeans with the new cK-logo patch that I designed with graphic designer Fabien Barron. Calvin loved the new ID and, together with Kate Moss, it became iconic of the young, new Calvin Klein brand.

When Kate first walked into Calvin’s office, I mistook her for an intern. She was tiny, like there aren’t enough zero’s to describe the size of her hips. When Calvin said she was fabulous, I argued that she was too small for our fashion show samples. He told me to make it happen. All our jeans came in a size 6, falling way low on Kate’s 00 hips and revealing her underwear. This looked kind of sexy, so for the Spring ’93 fashion show all the models wore their CK underwear as outerwear and inexplicably this look became symbolic of a new kind of sexual empowerment for an entire generation.

The sexual revolution of the sixties and seventies that Calvin straddled and rode in new directions, seemingly empowered my generation of women. While his ad campaigns took down barriers of prudery by celebrating the naked human body at its purest, they may also have encouraged sexual prowess. Men like Weinstein, Clinton and Trump might have wished that every woman was like Lisa Taylor in that famous Helmut Newton shot. The one where she sits with her legs spread and a come-hither smile on her lips. Did they imagine themselves as the shirtless guy, ready to respond to her invitation? Reality was the other way around --it was the men’s needs and urges women were expected to fulfill. Men dictated what our sex drive should be, like tit for tat, on the road to our mutual success. Until now when, more than four decades after that symbolic photo first came out, there is consensus that women’s sexuality has been grossly misread by men as complementing their own --inevitable, casual, and reflecting a mutual understanding of power and submission. It seems to have come as a surprise that we didn’t enjoy the sexual revolution if we weren’t actually in control of it.

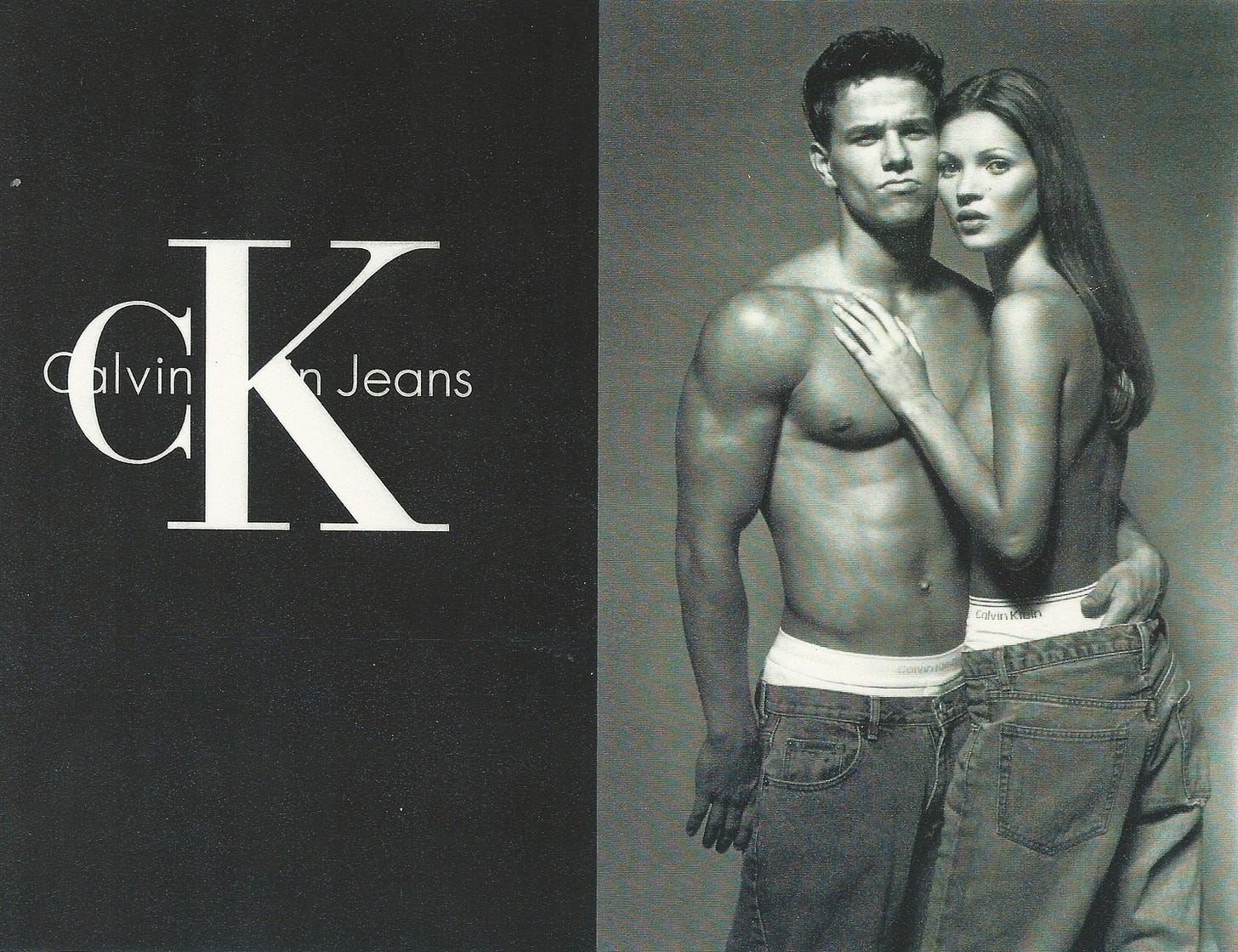

Even before the recent #metoo movement, Kate Moss revealed how the first CK shoot with Mark Wahlberg intimidated her. I’ll never forget how horny Mark was, as he stood in the middle of the showroom where we rehearsed our Spring ’93 show, surrounded by models in various stages of undress. He turned to Calvin and said, “Man, I want your job!” Calvin smiled, but he didn’t really seem to get that Mark felt he’d landed in the candy store. A few weeks later, Kate, age seventeen, shot the famous Times Square posters that looked like she was about to have sex with Marky Mark. In reality she didn’t vibe with Mark and was reluctant to take off all her clothes. However, she was under contract with CK and shot the ads that made her famous, crossing that barrier so many women have crossed when they endured random sexual encounters as an inescapable element of their career track.

Calvin is proud of his part in the sexual revolution and challenging the prudery and sexism of the fifties for women as well as gay men. Now, in the context of the twenties, his works is starting to look dated. Except perhaps for CK One, a non-gender-specific collection and scent, which back in 1993 was a harbinger of things to come. “We are one, and our sexuality is one,” Calvin said after a huge unisex fashion show with 300 male and female models at the Hollywood Bowl. Thirty years later, and iconic to the new century, identifying as non-gender is a human right. CK One could have been the vehicle that broke taboos and generated more tolerance, but unfortunately Calvin’s next 1995 campaign was accused of looking like child pornography -- a series of ads that, for the first time ever in Calvin’s messaging, gave the impression that his models were victims rather than emboldened individuals. This highly controversial campaign backfired on Calvin and became a platform for the conservative right and their agenda to push women back to traditional roles and conventional sexuality.

At work, Calvin, like so many male designers, surrounded himself with women. Perhaps this stems from tradition. The movie Phantom Thread, set in London in the forties, paints a realistic picture of a sole male designer in a world that is otherwise devoid of men. According to The Business of Fashion, 70% of the support system in leading fashion brands in 2016 was female whereas they took up less than 25% of the leadership roles. Paradoxically less than 7% of fashion students at fashion colleges like Parsons New York, are men. Even in a business that is driven by women consumers, there is still a distinct glass ceiling, which starts right below the top, at that single coveted position of the label that carries the designer’s name. When I was at Calvin there were at least six designers who designed Calvin Klein Collection and six designers who worked on CK. The one designer who went onto a launch brand of his own in New York City, was Narcisso Rodriguez. Since Calvin retired only young men have been at the helm of the brand’s design studio.

If it weren’t for the women behind Calvin, there would have been no Calvin Klein brand. And I am not talking about models like Brooke Shields, Jose Boudain, Christy Turlington, and Kate Moss, and muses Kelly and Marci, who he positioned as idols painted by himself. It was the hundreds of talented, creative, smart, visionary, dedicated but anonymous career women – designers, seamstresses, pr’s, marketers, stylists, producers, analysts, and so on, who made it happen.

The recent movement that exposes men who sexually abused women in the workplace is arguably a form of empowerment, yet it is inextricably linked to victimhood and hardly reflects our true power as the pillars behind so many successful men and companies. The next step in women’s empowerment is to give and get credit where credit is due. And if necessary, grabbing it by the balls.